Justice and injustice do not escape art; indeed, justice in art appears not only as a symbol of abstract morality but also weaves itself into human truths, ethical dilemmas, and the powers that define it. Throughout the centuries, art has offered a mutable perspective on justice—from law as social harmony, solemnly represented in ancient and medieval works, to a justice imbued with sterner, more institutional attributes through symbols such as the scales, the sword, and finally the blindfold.

This iconography, unchanged until the eighteenth century, eventually ceased to be celebrated and at times even took on a satirical hue, voicing a popular, critical “common sense” toward a legal power seen as distant and often corrupt.

Honoré Daumier explored this social critique by depicting lawyers and judges in caricatured attitudes to show the distance between the judicial system and the people, alluding to a cynical, money-oriented judicial power. His drawings—collected in Le Gens de Justice and published in Le Charivari—illustrate the dynamics between lawyers and judges with irony and realism. Later, this satirical vein spread to Germany and the United Kingdom, where the magazine Punch continued the critique of the judicial system and, similarly, William Hogarth examined British legal corruption, as in his series of engravings The Trial.

https://www.eamesfineart.com/artworks/11692-william-hogarth-bambridge-on-trial-for-murder-by-a-committee-1803/

Alessandro Casale’s attention to the forensic world represents a rare and original contribution within contemporary art. While artists have often addressed political, social, and religious themes, few have chosen the legal environment as their primary subject. This makes Casale’s vision particularly interesting, as he explores the concept of justice not through abstract symbols or idealized figures, but by drawing the observer into a courtroom—a space that is both solemn and rife with contradictions.

Trained as a lawyer, Casale understands the weight and complexity of that world, and in his paintings he portrays it as a theater suspended between authority and fragility, where judges and lawyers confront the tension of the accused. He emphasizes a separation between the judges, positioned high like almost sacerdotal figures, and the anonymous, indistinct crowd of participants populating the lower part of the canvas; in doing so, he reinforces the sense of detachment and inaccessibility with respect to judicial power.

Casale’s scenes vibrate in a motionless time, as if suspended in limbo. Everything seems to await a verdict that never quite arrives, and the viewer is drawn into an atmosphere of suspension and doubt—a process that never truly approaches the truth.

Faces lack precise details; people are reduced to archetypal figures. They appear as inscrutable masks, with vacant eyes gazing elsewhere or fixed on the viewer with a look that perhaps awaits a second judgment, another chance, making the observer feel judged in turn. The bodies seem almost to merge into one another, like a human magma in which individuality dissolves in favor of an amorphous collective.

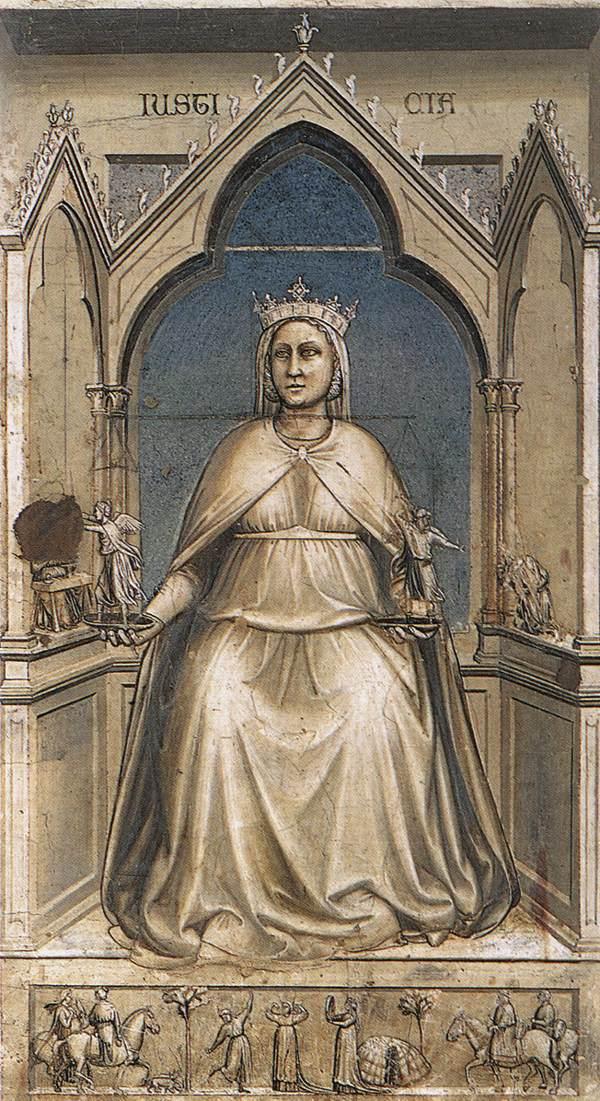

In past allegories of Justice—such as those by Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel or by Raphael in the Vatican Rooms—justice was represented as a divine, elevated virtue, often embodied by idealized, angelic figures. Raphael, in The Disputation of the Sacrament and The School of Athens, constructed compositions that expressed the order and coherence of an absolute system of values in which justice was part of an orderly, rational body of knowledge.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giustizia_(Giotto)#/media/File:Giotto_di_Bondone_-_No._43_The_Seven_Virtues_-_Justice_-_WGA09270.jpg

In some of Casale’s paintings, the courtrooms resemble temples—though profane ones—places with a sacred aura yet devoid of redemption. We do not find heroic figures or judges portrayed as martyrs of justice; rather, the artist shows men and women participating in a ritual permeated by doubt, relativity, and an unsettling questioning of the very meaning of judgment.

His approach is more existential and philosophical than caricatural, although at times rather grotesque aspects are exposed. He imbues his works with a subtle irony mixed with an unease that raises more questions than it answers. Casale is not interested in judging his subjects; he observes them, inviting us to examine the cracks and ambiguities of the system. The figure of the lawyer, in particular, is depicted as the bearer of an unstable truth—always open to reinterpretation and, at times, to deception.

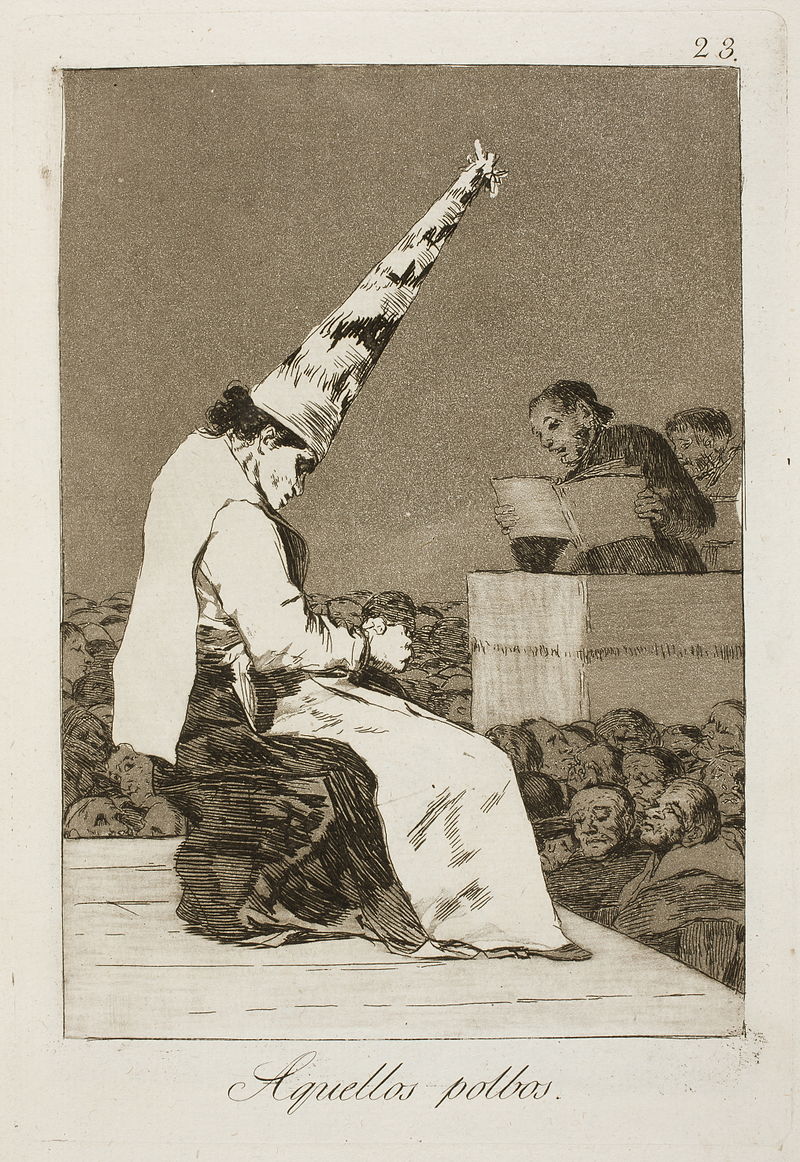

Central in this cycle of works is not so much the individual case—the hearing, the trial—as it is, once again, the inner landscape, that “other” temporal dimension characteristic of the artist’s poetic vision, which in this case suspends us in yearning, anticipation, doubt, and an emotional vortex—a kind of internal trial. In this context, Casale seems to inherit the visionary, dark approach of Francisco Goya, who with his Caprichos delved into the shadows and contradictions of the human soul.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_capricci#/media/File:Museo_del_Prado_-_Goya_-_Caprichos_-_No._23_-_Aquellos_polbos.jpg

However, while Goya employed caricature to expose irrationality, Casale prefers a rarefied atmosphere in which the viewer is drawn into a suspended dimension, devoid of answers and steeped in a moral void.

Alessandro Casale thus invites us to reflect on the concept of justice as a complex representation of power, where the true verdict always seems elusive and judgment remains suspended. He offers no answers but instead poses uncomfortable questions and disenchanted reflections: Is it truly possible to judge?

Websites:

https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/arts/peinture/william-hogarth-the-rake-s-progress