Nothing fascinates more than that which exists solely as a possibility, that which one cannot assert with certainty exists. Dream and mystery intertwine in art—as in our imagination—hovering between the visible and the invisible to offer new levels of interpretation.

At the beginning of the century, Marc Chagall plunged into a personal, fantastical world, giving form to inner visions in which intense colors and floating figures reveal a poetic and nostalgic dimension. His flying animals, houses suspended in the sky, and distorted characters serve as symbols of an inner universe—a realm of emotions in which reality and imagination merge into a visually charged narrative. Chagall creates an “oneiric world” where every element is imbued with meaning, a microcosm inviting the observer to explore an intimate, spiritual reality.

The advent of psychoanalysis by Freud and Jung breathed new life into this quest. For Freud, dreams are “the royal road to the unconscious,” a notion that would inspire André Breton in founding Surrealism. In 1928, in his manifesto Le Surréalisme et la Peinture, Breton defined surrealist art as a means to access an irrational world, proposing the dream as a superior reality free from logical constraints. Thus, Surrealism drew on psychological theories and ventured into the profound dimensions of being.

Salvador Dalí stands among the revolution’s key figures: his works, such as The Persistence of Memory, are populated by symbols that, defying the laws of physics and time, reveal the abysses of the subconscious. Through meticulous, hyperrealistic imagery, Dalí introduces elements like eggs, ants, and soft, malleable figures—symbols of repressed anxieties and desires. His painting, an almost obsessive analysis of the unconscious, sees the dream as a portal to both the collective and personal realms of the psyche.

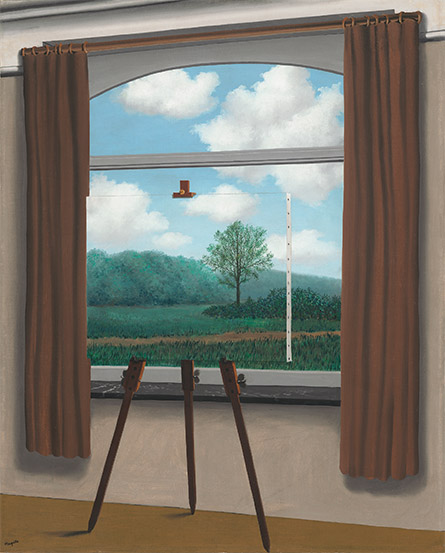

Beside him, René Magritte adopts a different approach, presenting a “rationalized” unconscious that destabilizes reality with cold, analytical logic. In his paintings, the apparent normality of objects is subverted to evoke mystery and absurdity—a method of questioning the very nature of reality. Magritte stated, “The mind loves the unknown. It loves images whose meaning is unknown, for the meaning of the mind itself is unknown,” suggesting that dreams allow access to deeper levels of the psyche.

In works such as The Human Condition, Magritte plays with the concepts of perception and representation: an easel depicts a landscape that merges with the actual scenery, highlighting the subtle boundary between what we see and what we believe we see. The painting Ceci n’est pas une pipe (this is not a pipe) challenges the viewer to reflect on the difference between reality and its depiction, suggesting that the world of dreams and representations is as real as ordinary perception.

Rather than portraying chaotic or intensely emotional dreamscapes like those of Dalí, Magritte prefers to evoke the dream with a cool, analytical logic—rendering the familiar as strange and the absurd as possible. His subjects—skies inside closed rooms, faceless men, flying fish—offer delicate, suggestive access to the unconscious, evoking a realm that is both mysterious and deeply unsettling. Magritte reveals the dream as a plane parallel to everyday reality, a space in which every image can assume multiple, profound meanings, overturning our understanding of the visible world and inviting reflection on the limits of perception: “Reality is never as it seems; truth is above all imagination.”

In Joan Miró, the dream transforms into a symbolic, fairy-tale language populated by geometric figures rendered in bright colors and elemental forms. Other surrealists, such as Paul Delvaux and Yves Tanguy, explored the territory of the unconscious with equally visionary poetics, striving for representations that, as Breton theorized, lie “beyond any conscious control.” In this psychic automatism, art becomes a vehicle for expressing deep thoughts and impulses, liberated from the constraints of reason.

In the postwar period, American Abstract Expressionism resumed the surrealist legacy, shifting the focus to the artistic gesture as a means of expressing the unconscious. Jackson Pollock, with his signature dripping technique, transformed the canvas into a mirror of the soul—a place where the chaos of his psyche materialized in abstract, fragmented compositions. In his famous declaration “Painting is a discovery of the self,” Pollock encapsulated his vision of art as an inner journey, a creative trance, almost shamanic, that unveils the hidden impulses and “demons” of the unconscious.

Pollock’s works, such as Number 27 (1950), embody this approach with a chaos devoid of a central form or predefined structure, where gesture and color merge in a ritualistic dance upon the canvas, transforming the painting into an extension of his psyche. As Palma Bucarelli wrote, Pollock’s art becomes “the image of that gesture and its emotional power,” a visual manifestation of inner movements, chaos, and the primordial energy that dwells within humanity.

In contrast, in Casale’s works—such as Rovi—the presence of the unconscious is more subtle, mediated by a naturalistic sensitivity. While Pollock uproots every form to surrender entirely to impulse, here forms emerge and dissolve with delicate grace, suggesting a more harmonious relationship with nature and the inner self. Casale’s technique might seem less radical, yet it is driven by a similar intent: not to represent objects, but rather to convey processes, emotions, and states of mind. The intertwining brushstrokes and patches of color convey a sense of immersion, as if inviting the viewer to lose themselves in a mental landscape.

Casale accesses the unconscious in a less obsessive, almost contemplative manner: his paintings invite silent reflection, an inner dialogue in a state of quasi-religious introspection, and a journey that is exploratory rather than frantic—as if he sought to reestablish a primordial connection with the environment. Sinuous lines and organic forms evoke flora and the cycles of nature, creating an inner garden where the self manifests in a subtle, peaceful way, conveying continuity.

In works such as Migrazioni (2010), Casale embraces the suggestions of Miró and Klee, evoking a suspended, timeless dimension in which organic forms and intense colors hint at a plurality of inner worlds. In doing so, he reconnects with the symbolic language of the unconscious, opening up a reflection on the very essence of human experience, “beyond the visible,” as Breton liked to say.

From Chagall to Casale, the representation of the unconscious evolves into a constant dialogue between the inner and the outer, giving form to the immaterial. In this exploration, art becomes the voice of hidden worlds, inviting us to reflect on the limits of perception and the enigma of existence. Through dream and imagination, the twentieth century opened a window onto the unspeakable, revealing a language that—at the intersection of dream and reality—continues to speak to our deepest, most hidden depths.

Web Sources

Fig. 1: gagarin-magazine.it

Fig. 2: analisidellopera.it

Fig. 3: barbarainwonderlart.com/la-condizione-umana-di-rene-magritte/

Fig. 4: ansa.it/canale_lifestyle/notizie/tempo_libero/2018/10/09/pollock-perche-number-27-e-un-capolavoro-di-espressionismo-astratto_287ce69c-8a3c-49fb-a459-c9a74c4ca0aa.html